I’ve been working with Git for some time now, probably 5 years or so. Tried (or been forced to) quite a few other VCS-es before (CVS, SVN, Mercurial and even some Perforce). To be honest I wouldn’t like going back to any of them. Git is so good and gives you so fine grained control over your repository you won’t miss your old VCS. It lets you work in a workflow that’s ideally suited for you, yet allows keeping everything clean and predictable in public/release code.

On the other side, I see a lot of people struggling with it at the beginning and desperately looking for some advice how to structure their repository. What they usually find is GitFlow process described by Vincent Driessen in his post: A successful Git branching model. While at first it looks really nice, it has few misconceptions about how Git works and makes your work a bit painful after your projects grow.

In this article I want to show you a simpler process that works really great with small teams and linear development, but also scales to big teams with simultaneous releases you need to support at the same time.

Everything goes to master, develop is a waste

Every new feature and bugfix should end up in master. There’s no need in Git to have a branch if you want to only tag commits. You can tag any commit and it doesn’t have to be on any particular branch. So in GitFlow “nomenclature” you could use only develop branch and remove master altogether, but there’s one issue with that. Everybody in the world expects to see latest changes in master after they clone your repo. Every tool out there considers master as the current development branch. So just delete this develop nonsense and make master tip source of your latest and greatest features.

Now, you don’t want master to be full of interleaving commits, so you do all your work in…

Short living feature branches

Each time you start a new feature it should begin with a new branch. Naming is not important, they won’t last long. Probably a day or two.

The way I work with these is that I create a lot of commits with half-baked code and informal messages. I really create a lot of mess. Sometimes just to switch to another branch and check things out or to help someone out with his code. But when a feature is ready I do a careful rebase over origin/master and squash all this stuff into one or two meaningful commits that clearly represent the feature.

Of course, you can introduce some more formalized process, especially when more people work on feature (branch). Still remember, that local commits are for free. Nobody sees anything until you run git push and you can always clean up the mess before pushing.

All these feature branches end up in master via merge (of course after rebase to keep history clean). Do it as often as possible. The more often you integrate, the better.

Oh, and after merge (with fast-forward) you should delete feature branch. It’s worthless to keep them around if you made commit messages meaningful and track features/bugs in a bug tracker. They just add noise when browsing history.

Releasing

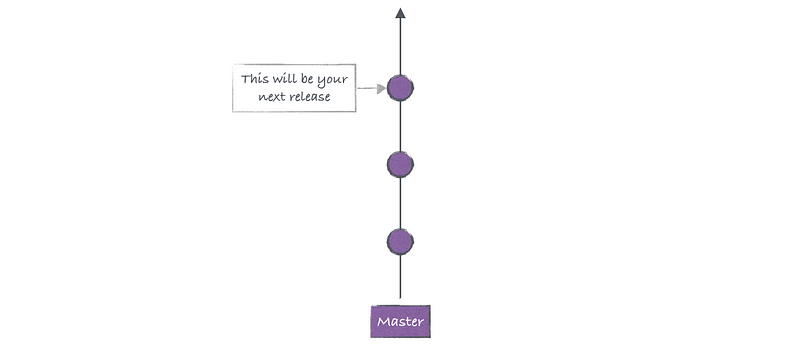

All you have to do when releasing a new version is to create a tag on master. Mark commit you consider ready and that’s it. git tag v1.0.0 is really enough. You don’t need any release branch yet. Just create tag, check out and build release package.

After release, you simply go back to master and work as usual on your new features.

Release bugfixing

So far everything was very straightforward, but what to do if you need to fix a bug in release while you already have new features on master?

Simple. Just create new branch release-branch-1.0 on commit tagged with v1.0.0. Check it out and do your bugfixes, just like you would do it on master. When everything is ready you create new tag v1.0.1 and release.

Remember that release branch is, like master, always in a releasable state. Things not ready for production should not land here or should be disabled with feature toggle.

Back(Forward)porting bugfixes

After fixing a bug you’ll of course want to incorporate it also on other supported versions that apply. There are 2 ways you can do it — by merging or by cherry-pick.

Which one should you choose depends on how many versions you need to support and where the bug was initially discovered and fixed. If the bug was fixed on release and you only need to support master — no problem, just merge release branch back to master and do it after each bugfix. Things get more complicated when you need to push it to more places or bug was fixed on master and you want to backport it to older versions. Then you need to cherry-pick changes to all relevant branches.

I would use cherry-pick anyway, just to be consistent.

Many simultaneous releases

Now what’s really good about this model is that it scales to really big projects. We’ve been using it on projects with 3 simultaneous production releases and some more in pre-prod testing. The project was really large with more than 100 developers working on the codebase. Yet this GIT process worked pretty well. We just had many open release branches which were receiving bugfixes and some small improvements. Some of them were ported to future releases, some were backported to older ones. Everything worked nicely.

Summary

I’m sure there are some weak points in this model and it might not fit well in your case. Though it worked very well for us on small and large projects with a centralized master repository. So if you’re still not sure how to structure your next GIT repository just give it a try.